There are not few theories about the way in which it has been designated, from the time of the natives, the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors led by Christopher Columbus, to the ruling of a decree of the Hispanic Crown.

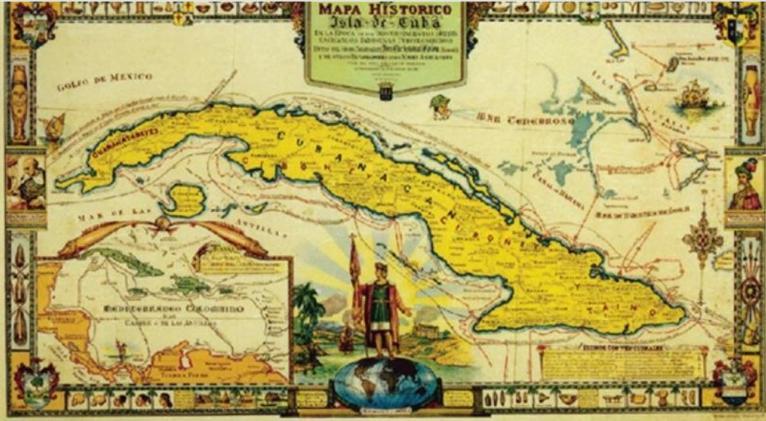

The origin and meaning of such an appellation, according to some, goes back to the word Ciba, which among the Tainos who inhabited this territory meant “stone, mountain, cave.” But there are those who believe it could have come from the Taíno word cohíba.

And there is even a remote possibility the name comes from the Arabic word coba, which means mosque with a dome, because it bears resemblance to the mountains that Columbus visualized when he landed in the Bay of Bariay.

Another theory points out that the Island’s location is the Caribbean relates it to a derivation of the Taíno word Cubanacán, which according to the Oxford Dictionary means “place in the center.”

Whatever any of these hypotheses is real, it is worth adding that the Genoese Admiral baptized Cuba as Juana, in homage to the daughter of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile.

On February 28, 1525, by Royal Decree, the monarch decided to give Cuba a Hispanic name and in her own honor called her Fernandina. However, it did not have such acceptance among the majority of those who were related to the territory conquered overseas and even the chroniclers of those times showed little motivation to accept that name.

In the mid-sixteenth century, the name recorded is Cuba, and not Fernandina, at least in official documents.

The Chapter Acts of the Havana City Council (1550-1565) attest to the above. From 1550 to 1554 Fernandina always appears, but already in 1555, when the pirate Jacques de Sores sacked the city, the reviews omitted all reference to the name of the Island.

Cuba has been the name of the Island since the Council of January 3, 1556, although there were two exceptions in 10 years.

In all this history there is something very curious. The Waldseemüller’s Nautical Chart of 1516 calls Terra de Cvba the territory currently occupied by the United States.

Scholars of the subject, such as Professor Ricardo Padrón, believe that Columbus was convinced that he had discovered an integral domain of Asia and when he was certain on his second trip to America that the coasts he was exploring were those of an island, he denied it and made swear to his crew that Cuba was continental and not insular.

Such an assertion had repercussions on the map of the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller in 1516, at a key moment in which there was talk of a new land but few knew what it was like.

In 1507, Waldseemüller created a famous planisphere in which he, for the first time, designated the lands of the New World with the name of America in honor of the Italian navigator Amerigo Vespucci as the first European to discover those territories.

But in the Marine Charter (La Carta Marina) of 1516, he omitted the name America for the continent and called the territory occupied by the United States Terra de Cuba-Asie Partis (Land of Cuba, part of Asia), and assigned the encounter between cultures to Columbus in place of Vespucci.

In an era in which knowledge and information were ambiguous, German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller’s confusions were even logical.

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Escambray reserves the right to publish comments.