Today, 64 years after the event, with the economic, commercial and financial blockade hindering the progress of our agricultural and food program in a criminal manner, Cubans are united in the effort to honor with results, and not only with projects, the significant event that from its beginnings went beyond the realization of a promise in favor of social justice. It also had in its sights the liberation of the country’s productive forces and its development.

Fulfilling a core objective set forth in the Moncada Program was a matter of honor, and ratified that the Revolution and its Leader were authentic, that this time “it was for real”.

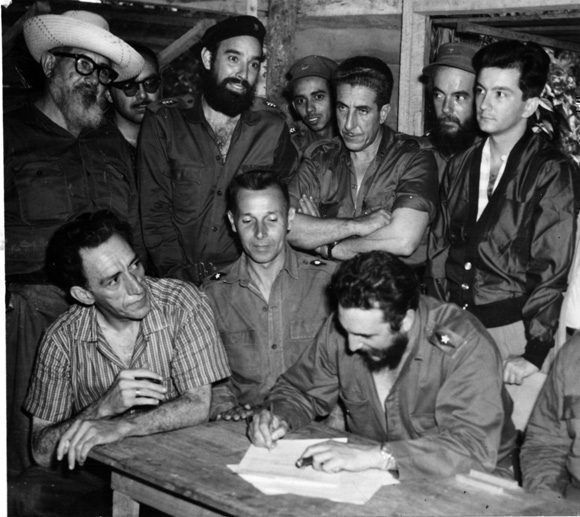

With the so-called First Agrarian Reform Law, some 100,000 tenant farmers, sharecroppers and squatters acquired the ownership of the land they had worked without rights, from sunrise to sunset, even all their lives, and the date in May when the document was signed in the happiest act of the mountains became the Day of the Cuban Farmer.

Years later, 25 years after the event, Fidel Castro specified:

“It was not only the delivery of land to the farmers who worked it, it was not only the liberation of agricultural workers; but in a whole set of fundamental aspects we could say that on May 17 began the liberation of our farmers and our agricultural workers.”

The Leader pointed out the contribution he made to equity and social justice, he also underlined his contribution to the end of the phenomenon of latifundism, a deforming structure favoring sugar monoproduction and when more cattle raising, in large extensions of generally unproductive lands, in the hands of a few owners, national oligarchs and U.S. private owners.

With areas dedicated to unproductive large estates of the sugar and livestock industries, 75 % of the country’s agricultural land was occupied.

In addition, Fidel was well aware that ending latifundia was not only about ending a deformation that slowed down the economy, but also had to do with political sovereignty. 1,100,000 hectares (ha) of the best lands were in the hands of North American capitalists, most of them covered with weeds for their convenience. These were interests defended by the hegemonic power.

The assessment of those who believe that the 1959 Agrarian Reform Law gave the green light to the transformation of Cuba’s economic and social structure, giving way to a genuine development process is very accurate.

It is known, however, how much Cubans have had to fight against the obstacles: sabotage, criminal actions, invasions, counterrevolutionary wars, illegal and irrational economic restrictions… that the United States has organized to block the plans of the Revolution since then until today.

It is necessary to consider the meaning of land tenure for the peasantry and agricultural workers, sectors that have been mercilessly exploited for centuries, impoverished by chronic hunger, curable diseases, marginality, in short, extreme poverty, with high illiteracy rates and no legal rights of any kind against the excesses of the landowners. The dark night became a radiant dawn.

This Law granted the non-seizable and non-transferable ownership of land to all settlers, sub-settlers, tenants, sharecroppers and squatters occupying plots of five caballerias of land or less.

Its legal basis was found in Article 90 of the 1940 Constitution, which established the prohibition of latifundia, although it had never been able to be translated into an optional document to enforce this intention of justice. Only with the triumphant Revolution would it be fulfilled.

It was put into effect on June 3, 1959, after it was issued and signed in La Plata. Gradually but without stopping, it gave the peasantry access to mechanisms of social and material aid, as a priority, as well as to education and culture, which were part of the Moncada Program linked to the sanitary projects.

Another precision of the historical document is that besides prescribing the latifundia, it set a limit of up to 30 caballerias (402 ha) in the amount of land that someone could own as a natural or juridical figure.

Exceptions were made for larger estates, whose owners demonstrated a high level of production and productivity, although the definitive limit for these was up to 100 caballerias.

And something very important and sovereign: only Cuban citizens or companies formed by Cuban citizens could own land.

This transcendent law was a cleanly legal act, inspired by the progressive Magna Carta of 1940, which had been abused and unfulfilled by the tyrant Fulgencio Batista.

It was strict in the elaboration of the legal articles that supported it, in line with the practices of Cuban and universal jurisprudence. And above all, it offered due compensation to all the expropriated landowners. There is nothing to reproach him for in those terms, except for the fallacies invented by the bad faith of the usurpers of power, already known.

Challenged by the imperative need to achieve the development of agricultural entities, agricultural communities of workers and peasants, to guarantee the necessary food sovereignty, to increase production within a sustainable economy that lives in harmony with nature, Cubans feel that there is still a long way to go to live up to all that the Law offered at the time.

And it is not to deny the achievements and developments in encouraging stages, the changes in life, the humanization and beauty that today beats in those territories. Only that now they are more difficult to appreciate in the midst of the rawness of the present that are far from yielding to anyone, although they hit hard, it is not denied.

The path has not been easy, nor is it at this moment, something that everyone knows very well. But the challenge has been accepted and the option is to work tirelessly and correct mistakes. Change what is necessary. That marvel of the First Agrarian Reform did not come for nothing.

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Escambray reserves the right to publish comments.