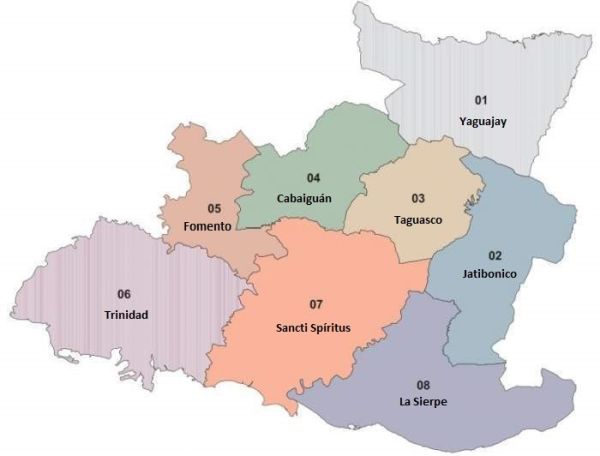

When American Mr. George K. Harper decided to invest in the cultivation of rice in La Sierpe, he came with a sure aim. He had already heard about the quality of the cereal produced in the southern areas of that territory —nowadays, one of the municipalities of the province of Sancti Spiritus, in central Cuba. At the beginning of 1950, he was already doing business with the representatives of the Valle-Iznaga family, owners of a large part of those lands.

It is said that in order to ease the business conversations, Mr. Harper offered a pack of Marlboro cigarettes to his interlocutors, and only when the red and black container was almost empty, an agreement was reached: he would keep 200 caballerias (26 840 400m2) —including Peralejos and Romero localities—, in exchange for properties he owned in the western Cuban province of Pinar del Río.

Some time later, Mr. Harper began the preparation of the lands. He built a dryer place in Romero and dedicated some hectares to cattle raising, thus rounding off his investments in the region, where he also found cheap labor.

IN CONFORMITY WITH THE LAW

By December 1958, dictator Fulgencio Batista’s fait was sealed, as a result of the constant pressure of the Rebel Army, led by Fidel Castro, with the contribution of other revolutionary forces. On the other hand, foreign investors’ businesses in Cuba seemed uncertain.

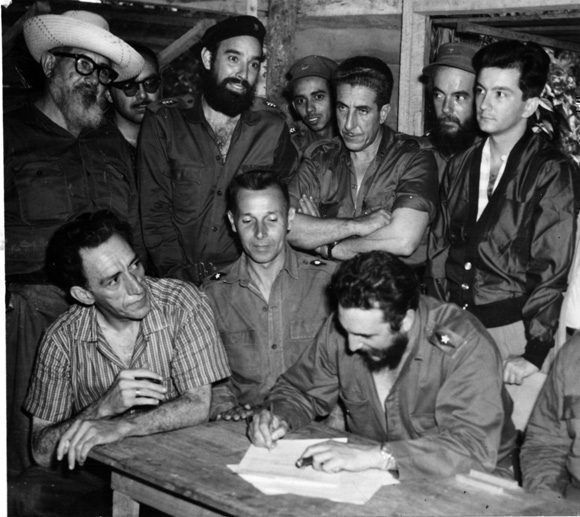

No trick of the US administration could abort the triumph of the Revolution, neither the military coup d’etat nor the provisional government … Every maneuver was pulverized. The Cuban Revolution became established and took action. Under the Moncada Program, the then Prime Minister Fidel Castro signed the Agrarian Reform Law on May 17, 1959, which proscribed latifundium and transferred to the State the properties owned by Cuban landowners, as well as by companies and foreign citizens, mostly from the United States. Mr Harper was among the ones who packed his bags and flew back to America.

On May 17, 1959, Fidel signs the Law of Agrarian Reform in La Plata, Sierra Maestra; in his speech that day, he was endorsing the nature of the triumphal process as a “true Revolution of the humble and for the humble”

The Cuban Revolutionary Government acted in line with international law if we consider the Special Resolution No. 626 of the General Assembly of the United Nations, signed in 1952, saying that “the right of peoples to freely use their wealth and natural resources and exploit them freely, given that it is an essential sovereign right and responds to the objectives and principles of the Charter of the United Nations”. The document also establishes “the compensation in accordance with the rules in force in the State that adopted these measures, in the exercise of its sovereignty and according to International Law”.

Twenty-two years later, the General Assembly sanctioned the Resolution No. 3 281, which reads: “The State has the right to nationalize, expropriate, or transfer ownership of foreign properties, in which case the State that adopts these measures must pay appropriate compensations”. Nevertheless, the US authorities refused to accept the compensations proposed by Cuba as nations like Great Britain, Canada, Spain, France and Switzerland did.

In her book Ideología y Revolución: Cuba, 1959-1962 (Ideology and Revolution: Cuba, 1959-1962), Dr. María del Pilar Díaz Castañón wrote that until September 1970, the United States’s Foreign Claims Adjustment Commission in Washington DC received 8,765 lawsuits —some were rejected, others reduced and a few increased— for loss of corporations and North Americans in the island. George K. Harper was one of them. He reported 1 643 535.03 dollars damages.

The claims amounted to a total of $ 3.5 billion dollars, without including certain major US firms and citizens with active properties before 1959 in Cuba who made no demands.

In addition to the UN resolutions, the measures adopted by the new Cuban Revolution were supported by two other legal instruments. On the one hand, the Fundamental Law of the Republic, approved in February 1959, which took up essential ideas of the 1940 Constitution, which instituted forced expropriation for reasons of public utility and social interest (article 24) and proscribed the latifundium (Article 90). On the other, the Law No. 851, of July 6, 1960, which regulated the forms of compensation.

According to Sancti Spiritus’s historian María Antonieta Jiménez Margolles (Ñeñeca), in addition to the nationalizations, the Government proceeded to the confiscation of property defrauded to public funds, and for this purpose created the Ministry of Recovery of Misappropriated Goods, directed by Faustino Pérez.

Experts say that the concept of confiscation differs from that of nationalization and does not presuppose compensations, like the ones which could be claimed today by Cubans living in the United States, under the Title III of the Helms-Burton Act, activated on May 2 by President Donald Trump’s administration.

This section of the legislation establishes the possibility for US citizens to promote an action in the US judicial system against persons and entities of third nations that invest in Cuba on nationalized properties and, at the same time, grants claimant authority to Cuban-Americans who were Cuban citizens when the properties were nationalized, which contradicts International Law.

THE OWNERS OF THE TOMATO PLANT

In the middle of the 1950s of the 20th century, a news spread mouth to mouth in the region: an American company, later on named Cotton and Masson, would encourage the cultivation of tomatoes in Peralejos.

According to Historia del municipio de La Sierpe (History of the municipality of La Sierpe) —a volumen so far unpublished—, the first 30 caballerías (4 026 060m2) of land were acquired by the Americans via a 200-pesos leasing each. Charles Morris, a native of Trinidad and Tobago, assisted them as a translator.

And so was born what locals named La Tomatera (The Tomato Plant). At the front door of the factory —says the text—, hundreds of people sometimes piled up to be received by Morris, in charge of choosing the necessary workers per day from whom he got 20 cents per capita for the contract arrangement. The working days were paid 2.46 pesos to men and 1.67 to women.

The fame of La Tomatera went beyond local borders to the point of being visited by Batista, who was welcomed in pomp by the US owners. They expressed their support for the president, who, in general, gave the keys of the Cuban economy to the foreign monopolies, mainly those from America.

THEY INTENDED TO STAY HERE …

Aquí pensaban seguir/ tragando y tragando tierra… (They intended to stay here / swallowing and swallowing land …) In this way, singer-songwriter Carlos Puebla described how the island was swallowed up by foreign capital and the corrupt governments of the day. But, he also wrote: Y en eso llegó Fidel… (But then Fidel showed up…)

Like in the rest of Cuba, the process of nationalization was also implemented in what would later be the municipality of La Sierpe and, consequently, the large rice areas, cattle farms and other cultivatons in the hands of American and Cuban landowners became part of cooperatives first, and later on of people’s farms.

The area where the community of La Sierpe was built belonged to the Piloto Farm, dedicated to livestock raising. His owner —named Talavera— left the country after 1959. Until now, it is not known if he —if still alive— or his descendants have filed any suit under the Helms-Burton Act protection.

A similar unviable demand could also be established by the relatives of Francisco del Valle —also holder of the American citizenship—, who used to own the Natividad Sugar Mill, one of the 36 nationalized on August 6, 1960.

At that time, the Valle-Iznaga family owned large expanses of land, much of which is today in possession of the Grain Company Sur del Jíbaro and its productive units, which also includes areas nationalized from Americans who came here to do easy business.

*Historian of La Sierpe

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Whatttttt… How can we find out about George k Harper?