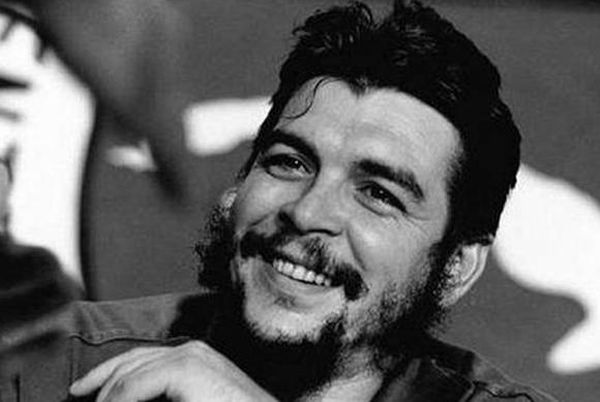

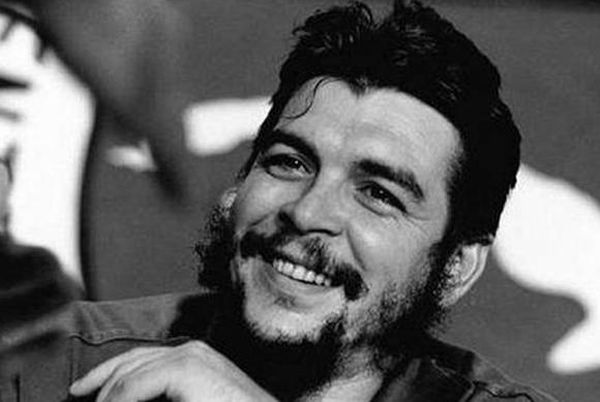

Every June 14, Cubans talk about Che’s perennial presence, his eternal youth and his ethical virtues, all expressed in phrases that are sometimes grandiloquent, but mostly respectful and moving

There are figures who never die, who cease being mere mortals to remain inevitably in history. People of thought, of character, of passion and sacrifice, who exalt human nature and attest to how much we can do as a species. Ernesto Che Guevara de la Serna is one of these figures.

It was no coincidence that his life should turn out like that. His asthma always accompanied him and made him a fighter. His father got used to sleeping up against the headboard of his bed, and Ernesto learned to control the asthma attacks lying on his father’s chest.

He didn’t always go to school, and was taught at home. However, he became independent and determined. He practiced sports and studied medicine. The books written about his life note that he attended practice with a fever, that he was never absent or stopped working.

For a long time, he observed, and also suffered, the Latin American reality. His travels in the region helped him to know which side he was on, and to which purposes he should dedicate his political thought. He saw the fall of President Jacobo Arbenz’s Guatemala (1951-1954), overthrown by a coup d’état orchestrated and financed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). He took an interest in the revolution in Paraguay and visited Bolivia, among other countries in the area. In Mexico he met Cuban revolutionaries. He traveled on the Granma yacht and landed on the island. He fought in the Sierra Maestra and became a Comandante. He was already known as Che by that time, and also as a revolutionary leader, with terribly strict discipline, those who were there assure us.

His mother was notified of his death on three occasions. “Three times we received the refutation and some reassuring lines. We aged in those two years. Every time I was relieved knowing that he was still alive, I became desperate again, remembering that the news was slow to arrive.”

But the guerrilla lived many more years, at least enough to become Minister of Industries, the advocate of voluntary work in Cuba, an expert in economics, a father, a politician and, above all, a transformer of the global left.

He defended everything he believed to be just, and was able to guide those who saw him as a leader. He went to the Congo because that war of national liberation was also his. His experiences served him in the revolutionary struggle in Bolivia and even so, it may not have been enough to him to have done everything he did, having decided to dedicate his life to others.

Today, 90 years after his birth, Ernesto Che Guevara is not simply a symbol of the twentieth century. He is the writer who left anecdotes of his travels and experiences in Latin America and the world. He is the economist, the politician, the Marxist, the son, the father, and friend. He is the man who is remembered for his ideas, his convictions, and his internationalism. The man to whom his followers have dedicated countless songs and poems. He is the paradigm that embodies selflessness, because, as Eduardo Galeano said: “He never kept anything for himself, nor ever asked for anything. Living is giving oneself, he thought; and he gave himself.”

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Escambray ENGLISH EDITION

Escambray reserves the right to publish comments.